Propaganda & how it was used to get Black people Enlisted in WWI

The Black presence in the First World War is nowadays quite well documented, although not widely acknowledged; but originally the British War Office, led by Lord Kitchener, was opposed to the use of Black soldiers. Kitchener’s posters “Your country needs you” were planned for white men.

Due to his racist vision of the Empire, he believed that Black faces would jeopardise the reputation of the army, that the Germans could mock “the mighty British Empire”. The Colonial Office and the King, George V, were keen to create the impression of a united, diverse and strong empire.

According to historian Michael Scott Healy from Loyola University in Chicago, “the idea of European, or ‘White’ racial supremacy, and Black inferiority” was very pregnant at the time. Racism towards Africans and Asians grew, fostered by theories such as social Darwinism, some scholars arguing that non-Europeans suffered from a “biological inability to improve” and were “destined” to labour for “Whites”.

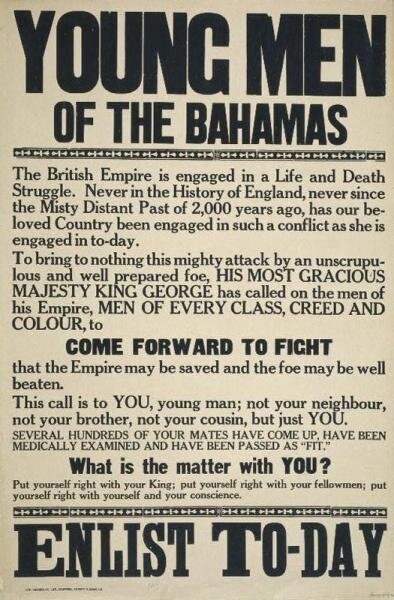

So new posters were soon targeted at the colonies. Indian recruitment posters were produced with blank strips to add text in local languages, Urdu and Hindi. Slogans called the West Indians to defend their “mother country”.

These soldiers were attracted by the idea to defend the Empire but also by the appeal of better wages, men being promised ‘very distinct advantages’ if enlisted, including medals, glory, discipline and free land at the cessation of hostilities.

Films, pamphlets and newspapers were used to fuel the recruitment, and women to craft letters in local press, until 1917. In December 1916, Brigadier General Blackden wrote in the Jamaican daily The Gleaner: “I hope that you women who have sons, brothers, husbands who are of fighting age will not hold them back. But will encourage them to come forward”. The press in England was also used to depict the “joyful” arrival of Black soldiers.

Off to fight for the Empire

From 1915, thousands of men from Barbados, Grenada, Jamaica, Trinidad and other colonies joined the British Army. The British West Indies Regiment (BWIR) was created in October 1915, most of them descendants of former enslaved Africans displaced to the Caribbean by slave traders. According to the Memorial Gate Trust, 15,600 men from the British Caribbean served in the Imperial Army during WWI – two third from Jamaica, the rest from Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, the Bahamas, British Honduras (now Belize), Grenada, British Guiana (now Guyana), the Leeward Islands, St Lucia and St Vincent. The regiment was composed of 12 battalions serving with the Allied forces, mainly in Palestine against the Turkish Army, in France and Flanders.

The islands were also requisitioned to send commodities like cotton, sugar, cocoa and rice to England. The West Indian colonies contributed nearly £2 million from tax revenue and donations to the war efforts.

1.4 million men from British India were also enrolled in the Imperial Army. On its side, France recruited nearly 500,000 colonial troops between 1914 and 1918, from West Africa, Indochina and North Africa, and when the United States joined the war, nearly 400,000 African American troops were inducted into the US forces. In total over 2 million Africans were involved in the conflict as soldiers or labourers.

But the context was particularly cruel for brown and Black soldiers. The Germans accused Britain and France of unleashing “Africans and Asiatic savages”. The French were convinced that West Africans, supposedly more primitive, could “better withstand the shock of battle and experienced physical pain less acutely,” as historian David Olusoga reported. “This justified deploying them as shock troops in the first line of battle.” Britain applied racist recruitment rules even in its own army, rejecting some Indians for being “too lazy,” according to their ethnicity.

Thousands of soldiers from the Commonwealth transited via England to reach the battlefields, but by the end of the war Britain planned to send them back to their islands, often without any pension. Some of them remained in England however. While in 1914 Britain counted around 10,000 ‘Black’ people, by 1918 they were 30,000, according to historian Stephen Bourne in Black Poppies – Britain’s Black Community and the Great War, (The History Press, 2014).

This was just the beginning of a greater migration trend, growing with the Second World War, the reconstruction through the 1950s and 1960s and the decolonisation movements.